“Despite what you find in my bibliography, I am not a nonfiction writer who turned to fiction, but a novelist who got diverted into nonfiction when I could not get my novels published… All my writing has to do with the demonic element in modern science and technology…“

— Theodore Roszak, St. James Guide to Horror, Ghost & Gothic Writers

Discovery — really, rediscovery — came like a Frankenstein-forked bolt of lightning. There was, in one category, Making of a Counter Culture, upheld as one of the best travel guides regarding ‘60s resistance to the machines built out of World War II — mentioned in the same breath as works like Bomb Culture, a sampling of hors d’oeuvres that came teeteringly close to the source of the matter, the birth of the psychedelic open-arms free-love tree-hugger movement, defined in opposition towards the “dominant” culture. Then, way on down in Dewey’s Decimal System, there’s Flicker — a noided, sex-ed up, film academy superstar tour, equal parts noir, metafiction, “skin mag,” and ancient-religion treatise… Both made by one man and separated by only twenty-two years.

I will call this investigation not professional jealousy, barely out of that realm, but an academic interest — there is no biography or for that matter much scholarship at all on Roszak’s work (save for pieces that have appeared in this magazine). And I, like all his heroes, am drawn further into the nest, a wandering web of women, science, madness…

BIOGRAPHY

Theodore Roszak was born in Chicago, Illinois in 1933, his father a cabinetmaker. Theodore’s (Ted’s) namesake was his uncle, the Constructivist sculptor who made a name for himself after emigrating from Poland around 1910 and eventually sculpting the eagle atop the former U.S. Embassy in London. Roszak quickly departed the Midwest and his parent’s Catholic household — moving coast to coast, his undergraduate education came from UCLA in Berkeley and he then received a Ph.D. in history from Princeton in ‘58. His dissertation — “Thomas Cromwell and the Henrician Reformation.”

Roszak then becomes a little more difficult to track, teaching at Stanford for a few scant years before living in London to edit Peace News magazine. He moved back and forth— beginning his tenure as a history professor at California State University Hayward in ‘63, but certainly overseas in the winter of 1968— a typewritten schedule shows Roszak teaching a 6:30 class every Tuesday at the Icarus-like Antiuniversity of London. (The only instructor on Saturday? Ed Dorn.)

He finally settled down for a long tenure at Cal State and resided in California until his retirement in 1998 and his passing in 2011. He died on July the 5th. It was my 16th birthday, and it would take me another decade to find him.

PROBLEMS

I stop myself here to say that the problem is this — any amount of biographical detail, any collection of little factoids, all these disparate ideas, statements about a man’s life — mean nothing against the face of his works. For one, I wish to honor Roszak’s legacy, not retread old ground, old dry soil. Roszak believed in a gestalt— a seamless piece of fabric pulled across a man’s life, his swaddle and his shroud. He has convinced me through his study— and my study of him— that no part of him should be considered without the whole. Fiction links to nonfiction links to biography links to bibliography just as muscle and bone and tendon are connected. Roszak railed against the plain “fact,” the Cult of Information. It would be wrong to say his biography unlocks the content of his work, just as it would be wrong to say his bibliography could tell us his state of mind. We have, as literary archeologists, pieces— some fit, some don’t. The trick is putting them together in a sensible way and guessing at the rest.

We talk very often of a gesamtkunstwerk, the idea of a work of art that encompasses all art forms, a “total work,” somewhat more literally “all-encompassing art form.” Roszak approaches this directly by incorporating his insatiable mind and system of beliefs directly into all his work. If it helps, think of him as a half-professor half-hippie Ayn Rand.

(Lewis Mumford, one of Roszak’s idols, apparently inspired Ellsworth Toohey in The Fountainhead. Mumford is worth studying at the very least as a player in 1920s Melville revivalism… but I digress.)

In that gestalt tapestry there are certain threads worth tracing, of a brilliant color or unusual origin. Only by viewing them one at a time can we then begin to see them all at once.

SOLUTIONS (1960 – 1970)

Religiosity and its lack are forefront in Roszak’s mind — from his very earliest publication (a review of Thomas Merton’s translation of the great Taoist Chuang Tzu) he writes often and obsessively about our belief systems. Now it is no surprise that Roszak should focus so much on religion and specifically Eastern religions— he was after all a contemporary of Alan Watts, Allen Ginsberg, et al.,— but he breaks early and sharply with these figures by suggesting that Eastern traditions displace Western ones altogether.

Somewhere in the early years of his life Roszak found a distinct distaste for both Catholicism and Protestantism alike. My speculation on the ideas around anti-Catholicism is quite limited (something to do with making a life outside of his parents’ I suspect, but I have no proof). The evidence of the attitude, on the contrary, is aplenty— in at least four of his novels (Bugs, Dreamwatcher, Flicker, and Elizabeth Frankenstein) priests are portrayed as either outright evil or at best a major nuisance. It is, after all, Father Angelotti who imprisons our hero on the island in Flicker, and Father Guinness (the Irishman) who plots to steal the little girl’s powers in Bugs, and, and, and…

But it is the anti-Protestantism that is much more thematically complex. Though Roszak places heavy scorn on the Catholic profession especially in fiction (I think in part for the romanticism of it all), the Catholics are very rarely treated the same way in his scholarship. Instead, it’s the Protestant strain that receives his strongest salvos— not so much for their beliefs, I find, but for their indelible link to Roszak’s greatest enemy: The Enlightenment.

Scientific minds dominate Roszak’s field of view and ignite his wrath as if Blake’s Milton were a personally appointed hit list. (Indeed he stomps the brakes in Where the Wasteland Ends, a long philosophical exploration written in ‘72, to deeply study Blake’s fourfold vision). Recall that his doctoral thesis— and I speak somewhat as Roszak here— was on a fallen star of the newly-Reformed English monarchy, a man who engineered the execution of Anne Boleyn and destroyed a huge number of books and manuscripts in his effort to purge the kingdom of Roman Catholic influence. Another name that shows up quite often in these philosophical tracts is that of Francis Bacon, also an Anglican and the father of modern scientific thought… and it is moreso this role, partially informed by those religious beliefs, that Roszak finds in him great fault.

Why the Enlightenment? Roszak sits on an odd fence in history. He was just slightly too old to be a part of the “counter culture” movement — hippiedom is, for the most part, a young man’s game — but just the right age for prime academic positions and firsthand experience about the new wave. Similarly, his age put him in touch with pre-hippie America, an America freshly revitalized by World War II— the war won by mass industrialization & mobilization, technics & cybernetics, and— The Bomb.

It is these elements Roszak identifies early on as key aspects to oppose. Clearly he was possessed of these beliefs before his major publications (the editing gig at Peace News, the British pacifist bi-monthly broadside, came a few years before even Dissenting Academy, an essay collection he edited in hopes of academic reform towards New Left values.) But it is in Making of a Counter Culture that his politi-cultural considerations really come into their own shape.

Published in 1969, Making of a Counter Culture launched Roszak’s writing career to the forefront of American anthropological studies — but ultimately accomplished something more valuable for him, I think — a clear-cut set of ideas by which he believed society should uphold. Counter Culture offsets both the hippies and the new campus radicals popping up in California against the “technocracy” — a word itself with ties to Jacques Ellul, Christian anarchist and critic of the “techne” that had taken over postwar society at large. In it, Roszak identified aspects of the culture like new Marxism, gestalt therapy, even LSD culture that he thought stood a fighting chance against a consolidated monoculture intent on sapping the life of Americans. His innovation was not so much linking the movements by what they had in common but by what they all opposed. Which, perhaps, is how “counterculture” became such a useful and ubiquitous term. This is oddly one of his more cautious works. He welcomes, for example, the idea of psychedelics as a consciousness-expanding device, but criticizes Timothy Leary’s perceived hucksterism and cult-leader qualities. The other interesting thing about Counter Culture is its complete lack of foresight (our hindsight) — we know what became of the Esalen Institute, the French student movements, the Berkeley love-ins… but despite his few misgivings Roszak truly saw these counter-cultural movements as part of a real alternative to societal ills.

In the ‘70s, however, these movements suffered a devastating pincer attack that they never quite recovered from. The first chronologically was Charles Manson and his Family’s murders. The Manson murders were a nearly perfect simulacra of “hippie” culture — the Beatles, the music industry, long hair, communal living, et cetera — twisted to be a mockery of the clean escapism that was supposed to be a panacea to the capitalist way of life. The second rose, not out of the hippies as Manson, but against them from the start. His name was Ronald Reagan, anathema to anyone even leaning left-wing for decades, the crown prince of the new Western conservative movement. Both as governor and President Reagan set a new standard for America — an embodiment of the pipeline from Hollywood to politics. This left the hippies, proverbially, between a jock and a scar face.

Roszak saw this writing on the wall and took up his banner in Where the Wasteland Ends (1972). This is, as I alluded, his most well-thought-out and philosophical work, one of his longest. The title spells out his position quite clearly. The war, though not lost, is not looking good. The religious revivalism, the search for a soul of the modern man, the thirst is met with a barren wasteland of a degraded physical environment, a society that has little to offer its citizens and everything to take away, a place captured, destitute, a virtual prison, a closed, overly technological society with no way out. Unless…

Roszak leaves his reliance on real-world examples as he did in Making of a Counter Culture and goes purely by the signposts of his personal beliefs and his academic skills. And he is, for the record, a fearsome competitor. A strong commonality through all of his writing up to the 90s and beyond is his excellent grasp and usage of history and academic sources, beyond his favorite subjects (Blake, Goethe, Wordsworth, and Shelley — Mary) and extending even to his enemies (Newton, Bacon, Locke, and the whole of Protestant tradition more or less). Where the Wasteland Ends is a very odd and very powerful book. Setting himself against the culture of science and for a kind of fiery poetic wisdom to guide our sociopolitical beliefs is an attractive, even entrancing image.

And yet. The idea of a single rebellious mind against society is not what we were wishing for way back in ‘69. Goethe, Blake, Roszak – all of them had Vision, but only the last had the goal of dismantling the structures of objectivism, reductionism, and techne that he identifies as poisons to the common man. Unfinished Animal, hot on the heels of Wasteland in ‘75, essentially calls for a new human evolution— not one of physiological changes but psychic changes, that we should all become shamans with fiery visions of our own, ready to prophesy in the wasteland like John the Baptist (and mentions such figures such as Blavatsky as vanguards of this new evolution).

Roszak, having left his perch, having staked his claim against the world in favor of the theosophists and shamans, the preachers and the poets, finally publishes the first fiction.

PONTIFEX

A play written, but never performed — a play already performed, and hastily written from memory — a play planned in immaculate detail and staged exactly once — this is Pontifex, published in 1974 by Anchor Doubleday. What Pontifex is, which is a rather engaging fairy tale about an artist finding inspiration through the chaos of society, is much more interesting than what it isn’t — an endorsement of the old tactics Roszak had been attracted to in the late sixties. The novel, written in stage direction and dialogue, is pulled along by the appearance of The Old Boy, an unstoppable Dionysian figure who robs banks, beats police officers, downs liquor, and makes a pass at every woman who passes. He is not the hero — that role rather falls to a man named Adam. A painter by trade, training under the hard tutelage of the monk-like Pontifex, until he is possessed by the spirit of The Old Boy and begins painting murals of dragons that rear up and attack citizenry, sending them into orgiastic trances. Yes, Roszak lays on the symbolism… but it’s honesty about his beliefs, and it’s refreshing. Side characters and villains are fun and well-defined (the pathetic International Democratic Revolutionary Workers and Peasants Party of the World, and the Bronze-Age-Pervert-Adjacent General Thrasymachus Augustus “Bull” Pizzle). Meanwhile the setting (the novel — which it is — disguises itself as a play, as the play is put on in a lively utopian park that twists and turns dreamlike around the action) is a who’s who of countercultural types and stereotypes. Imagine The Village People but one is a Black Panther, one is a street artist, one is a beat poet, and so on… and in this colorful way he channels Pynchon in some of his best passages. The extra-narrative songs, poetry, and interjections — all quite good — help with the comparison.

The experimental style helps Pontifex explode off the page and linger in your memory — but it would be the gothic, the noir, Roszak would turn to next.

DREAMS & NIGHTMARES (THE 80s)

The next decade was a time of both expansion and contraction for Roszak — of both outward-looking as the youthful counter-culture grew and disseminated among the people, and of inward narrowing toward specific issues. Person / Planet (1978) is Roszak wading into the world-historical if we take “world” literally. It applies many of the philosophical concepts outlined in Where the Wasteland Ends not to youthful folly and Watts-adjacent spiritualism, but to more concrete and long-term examples like the family, the school, the city. In this he is more Mumford-like than ever, and again we see a delicate balancing of the rush of poeticism he finds so valuable and the carefully plotting academy scholar.

All very well and good. But this time period also marked a slight shift for Roszak in that his fiction regarding a topic came well before his nonfiction. Bugs, in ‘81, superseded Cult of Information as his statement on the rise of computers in the U.S. — and the message came tattered and bloodied.

Bugs as Roszak’s first “traditional” novel and fictional exploration is rather straightforward in plot and construction, but contains many of his classic repeating themes — there’s a somewhat careerist man swept away by a spiritual guide of a woman (check), a potent demon of a new technological device (check) and a cult discovered by our hero making use of lost rites and secret knowledge (double check). In Bugs’ case, ants representing a child’s drawing explode and burrow out of mainframes, leaving people behind as bloody shreds who try to resist. Their source: a little girl, frightened by a new tour of the government’s almighty computer systems, summoned them all tulpa-like out of nothing, which queues a lively plot involving both federal and religious attempts to steal this great new power from her. (I described it to the Editor-In-Chief of this publication as a cross between Evilspeak and The Exorcist, and the cover throws in a little smattering of Andromeda Strain… and you’ll be close.)

What remains clear, though, is that Roszak takes the quick-rolling prose from the Pynchonian wonderland of his previous effort and directs it more toward the direction of Stephen King. He finds his best footing when he straddles the two.

There’s a similar feel in Dreamwatcher (‘85), of pulp sensibility mixed in with Roszak’s personal philosophy (a slight sense of the paranoid superseded by an almost familial obligation to display a utopian vision). In this case the technology is one that does not really exist; an ability to see people’s dreams is on the line here, not only view them but shape them into therapeutic breakthroughs or horrific nightmares. Roszak’s interpretations of “dreams” and dream-states leans much more Freud than surréalisme as the protagonist infiltrates other’s dreams to become their lover, a literal transvestite Transylvanian shows up on the first page, sexy nuns threaten to sodomize themselves with the somnambulist, and so on. Perhaps even more explicit in Dreamwatcher is the ongoing battle of wits between Roszak and his admiration & distaste for the Christian church. Remember, one must have some respect for someone to call them an enemy.

And enemy isn’t the right word, exactly — the target of some dream harassment in the book is Mother Constancia, a South American nun blessed with incredible spirituality and gifts of meditation, depicted as being in a constant state of internal struggle between her Christian beliefs and an encounter with a burning quetzalcoatl deity early in her youth. In this, Roszak takes a somewhat softer line than earlier in his life — the two coexist, but only just. And there is no mistaking that the church elders are in line with feds and psychologists of every sort (and, let’s face it, occasionally they are). In that respect for Roszak there is no separation of church and state — both form control apparatuses that are necessary to rebel against — but the individual strands are extricated to form opposing forces in his fiction. Oddly, Dreamwatcher is brisk and light on details of the technology and conspiracy, which gives it an airy, giddy feel compared to his other work.

This marks a terminal split — the nonfiction will continue in the way of ecopsychology and environmentalism mingling with his firmly established philosophies (the Ecopsychology essay collection, in collaboration with Sierra Club books, and The Voice of the Earth.) Again, a decoupling of counter cultural values from individuals and movements to whole-earth politics. But the fictional elements of Roszak’s work would descend — after a chance attendance at a Berkeley lecture on film preservation — into the world of Flicker.

FLICKER (THE 90s)

In German, the book is published by the title “Schattenlichter” — shadow light. The “shadow light,” the FLICKER, is the subconscious control system interwoven into all moving pictures since their inception, with a secret war being waged between technicians of the apocalypse and those who would prefer movies not exist at all. Meanwhile, there’s a lot of legitimate (and fictional) film scholarship, scholarship through sex, tantric sex, something called “The Lonesome Lovesong of the Sad Sewer Babies”… need I say more?

I do, just to emphasize how all of Roszak’s strongest elements combine in the book. It is simultaneously immaculately researched and playful with the subject matter (Orson Welles resides Buddha-like over a dinner in one scene, and both Pauline Kael and Louise Brooks show up in one fictional iteration or another). The religious element also plays a large factor, though Roszak does a clever bit of deflection here by pitting an ancient heretical sect — the Cathars — against a strange Catholic order, both discovered by our film scholar hero. And, similarly to Roszak and many adjacent to the counter-culture sphere, Jonathan Gates (the protagonist) rises from dog days at a rundown California theater to a cushy academic job studying his favorite mystery cult director, Max Castle.

Part of why Flicker caught on, I believe, is that part of it reads like a film student went on an Indiana Jones adventure fucking his way across the continent. I promise I’m not overselling it— the book is, in some respects, lascivious. These randier elements are balanced across the taste buds by dashes of the mystery at the heart of the novel, the scholarship, the cast of characters… but the sex does bubble up quite frequently. (Don’t even get me started on what “the deep shot” is supposed to be).

For new scholars of his, this is odd at first glance — Roszak’s long marriage was completely blissful (revered Betty, also his primary editor and often-contributor). Two publications — 1969’s Masculine / Feminine and 1999’s The Gendered Atom — strongly promote feminism in the arts and sciences, and places women at the forefront of his new envisioned society. So, how is it that we are able to square up Roszak’s beliefs with the contents of Flicker?

THE FAIRER SEX

Roszak finally synthesizes his ideas of sexual relations and his distate for the objective god of Science in The Memoirs of Elizabeth Frankenstein (1995). The general gist is that the Frankenstien tale is retold from the eyes of Elizabeth, Victor’s doomed bride-to-be — but not just as the devoted and doting woman we see in the original. Roszak takes some minor liberties with Shelley’s narrative and charts the story of Elizabeth from her adoption to her death, making her the adept of a coven of witches (again, a familiar theme). It is Caroline Frankenstein, both Victor and Elizabeth’s mother, who initiates them into this cult and trains them in the ways of Alchemical Romance, with the idea being that the children trained in certain techniques would one day wed and produce a child free of lust. What does this mean? Well, more tantric sex.

It is revealed that through certain explicit alchemical documents that Victor and Elizabeth participate in “Feeding the Lions,” in which Victor is made to stare at Elizabeth’s privates throughout the night without sleeping, and other acts that are supposed to make their bodies the ingredients and vessels of a perfect child, one that would be born with the highest faculties of humankind.

Elizabeth Frankenstein is no less didactic than Pontifex or Bugs — the somewhat pesky narrator (Captain Walton still) and Elizabeth’s narrative clearly shows which side Roszak falls on. What the book does resolve is the tension left by Flicker’s lewdness: to him, sex is a rite, an initiative experience that opens doorways between the masculine and feminine intellects. Through Flicker we see examples of this working to Jonathan Gates’ advantage: on rereads, it seems less like Gates is fornicating his way through film scholarship and more like he would be helpless without a battery of women to help him unravel Max Castle’s mystery. Elizabeth Frankenstein is the idea of that rite gone wrong. After Victor and Elizabeth engage in an alchemical practice which leads Victor to rape her, he flees to Ingolstadt to eventually begin the story of Frankenstein. Elizabeth, meanwhile, has a painful stillbirth experience and wanders the Swiss countryside for some time — the feminine mirror to Victor’s failed birth of a new form of life. Victor Frankenstein is played up to be a fiend throughout the narrative (he goes on to grotesquely reanimate individual hands and faces by electrical galvanism and is said to have harvested the brain for his monster from his own dubiously sourced stillborn infant). Whether the idea is that Victor is driven mad by his alchemical failure or that he’s lost all his moral faculties in his search for life, I haven’t decided for certain. Whichever is the case — the book makes certain that the dangers of overobjectivity are real, and places a deadly cost on them.

(This point had been gestating for some time — In Liberation magazine, April 1966, Roszak argues in a review of The Experience of Marriage: Thirteen Couples Report that Catholic clergy should have no opinion or say on the sex lives of Catholic couples because their celibacy disqualifies them from the essential experience of sex. Just as, he says, “tone deaf people have no business theorizing about Stravinsky.” How’s that for a comparison.)

2000s AND BEYOND

The last stretch of Roszak’s contains two more works of fiction— The Devil and Daniel Silverman and the woefully unfinished The Crystal Child. As it is not in a completed state, I can’t say much about the contents of the latter novel, besides it being the Roszakian fiction entry exploring aging — but from the viewpoint of a child afflicted with a very unusual disease. To compare this to Flicker would be like comparing The Original of Laura to Lolita — it’s simply unfair.

The Devil and Daniel Silverman, however, was finished, and published, in 2003, and ultimately disappointed. The main conflict of the novel arises from a gay Jewish atheist going to fulfill a speaking gig at a hardcore Bible college in Minnesota before being trapped there by a once-in-a-lifetime blizzard. The best part of the book is Roszak winking at himself (the fictional speaker has a bestseller described as “Moby Dick from the perspective of the whale”). The worst parts are all the rest, with the book barely saved, as another reviewer pointed out, by a denouement at a frozen lake a la Dante. I don’t mind Roszak’s crusade against perceived cultural Christian threats, and I can forgive heavy-handedness, forgive wrong-mindedness, and forgive unfunny-ness, but not all three.

This period does contain, however, the valuable pair of Longevity Revolution and Making of an Elder Culture, harkening back to his bestseller. I find these books touching and precise, different from a lot of writing on America’s elder population (and much better than World, Beware!, a mixture of Roszak’s anti-techne philosophy and a relatively boilerplate anti-Bush argument). In them are combined his zealous academic mind, his poetic humanism, a touch of the personal — Roszak was 76 when Elder Culture debuted — and a very simple argument: inside every old boomer is a hippie, ossified, waiting to again return to their revolutionary roots. Even in age these ideas did not leave him, and especially at a time when elders survived years of isolation only to see growing acceptance of euthanization, the ideas ring loud and true.

Roszak was much more than his highlights— He had, between 1965 and 1995, as a teacher, a novelist, and a researcher, an incredible run. His entire life was dedicated to ideals he formed in his youth. At the end of his life — the end of our tapestry — he rejected traditional funerary services and asked friends and scholars to give speeches representing Aging, Education, Politics, History, and Family — tutor til the end. His influence — more invisible than explicit — remains, and reminds us of a time when a different America was easily envisioned, a time when poetics could permeate every aspect of one’s life. And even more than this — it takes a diamond-sharp mind to not only envision a New Jerusalem, but lay the bricks to its eventual foundation — and then tell a parable of its further construction.

BETTER MONSTERS OF OUR NATURE

A typical definition of “monster” is “an imaginary creature composed of incongruous parts.” By that definition, there are no “monsters” in Roszak’s works. Each threat, each demon is inherent to the techniques or sciences that are used to summon it, whether intentionally or incidentally — the monster parts in question are never incongruous. Frankenstein’s monster was created as a perfectly logical consequence of his dangerous methods. The hypnotizing flicker is the inherent magic of the movies. All computers are crushed beneath concrete to quell the Biblical plague of ravenous insects… These are the things, like them or not, in Roszak’s fiery vision, trapped in the books like an ant in amber. When a man, like Roszak’s heroes of poetics, of philosophy, those he points to as tools against technological progress— when a man like that gets the fire behind his eyes, will he capture it, cool it to a weapon? Or will he let it burn him blind?

***

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Having noted some errors and inconsistencies in Roszak bibliographies published online, I hope this serves as a guidepost for future study. The only finer guide to Roszak publications can be found in the Stanford University Special Collections and Archives. This would not be an essay of mine if I did not complain about something, and for this, it was that I had a difficult time accessing the materials in that archive remotely. However, I do list all the main publications here. The Stanford collection also lists many works-in-progress and uncompleted novels called, among others, Death Star Coming, Kind Uncle, Skygate, and The Seventh Thorn. Maybe the topics of those unpublished works will be covered in a future publication.

Entries in this bibliography marked with an asterisk (*) at the end are especially worth your time and study. Notes follow the entries when applicable.

Liberation Magazine, April 1966. “A Dozen Private Hells.” Review of The Experience of Marriage: Thirteen Couples Report, edited by Micheal Novak, Macmillan Company.

The Frog In The Well, June 1966. Likely attribution: The Institute for the Study of Nonviolence and People’s Union. Text itself reprinted from MANAS Vol. XIX No. 22. Roszak was published many times in MANAS as early as 1965, all the instances of which are too numerous to list here. They are available here.

Dissenting Academy, September 1968. Vintage Books, Random House. Roszak as editor. The final essay, The Responsibility of Intellectuals by Noam Chomsky, may be of interest.

Masculine / Feminine, 1969. Harper Colophon Books. Subtitled “Readings in Sexual Mythology and the Liberation of Women”. Edited by Betty and Theodore Roszak.

Making of a Counter Culture, 1969. Anchor Doubleday Books. Subtitled “Reflections on the Technocratic Society and its Youthful Opposition”. Nominated for a National Book Award. *

Sources, 1972. Harper Colophon Books. Roszak as editor. Subtitled “An Anthropology of Contemporary Materials Useful for Preserving Personal Sanity While Braving the Great Technological Wilderness”. Of likely interest to the reader of this essay: entries by Merton, Levertov, Norman Brown, Paul Goodman, Neruda, Wendell Berry, Marcuse, and Watts.

War Resistance, 1st & 2nd quarters 1972 — volume 2 — Nos. 40/41. “The Need for Persistence”, advocating for total nonviolent protest, letter written in response to invitation to submit.

Where the Wasteland Ends, 1972. Anchor Doubleday Books. Subtitled “Politics and Transcendence in Postindustrial Society”. The book notes that Roszak was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship between ‘71 and ‘72 during his studies for this book. Nominated for a National Book Award. *

Pontifex, 1974. Anchor Doubleday Books. Subtitled “A Revolutionary Entertainment for the Mind’s Eye Theater”. *

Unfinished Animal, 1975. Harper & Row. Subtitled “The Aquarian Frontier and the Evolution of Consciousness”. Inspiration for the cover art of this article. *

Person / Planet, 1978. Subtitled “The Creative Disintegration of Industrial Society”. Anchor Doubleday Books.

Why Astrology Endures, 1980. Robert Briggs Associates. Subtitled “The Science of Superstition and the Superstition of Science”. Unusually presented in “Broadside Edition”, 6” x 9” permanent pamphlet form. Text reprinted from The Boston Monthly, October 1980.

Bugs, 1981. Doubleday.

Dreamwatcher, December 1985. Doubleday.

Cult of Information, 1986. Pantheon Books. ‘86 edition subtitled “The Folklore of Computers and the True Art of Thinking”. A revised and expanded edition was published in 1994 by University of California Press, now subtitled “A Neo-Luddite Treatise on High-Tech, Artificial Intelligence, and the True Art of Thinking”. Since there was no title change, I felt a new entry was unnecessary, but both versions receive the asterisk. *

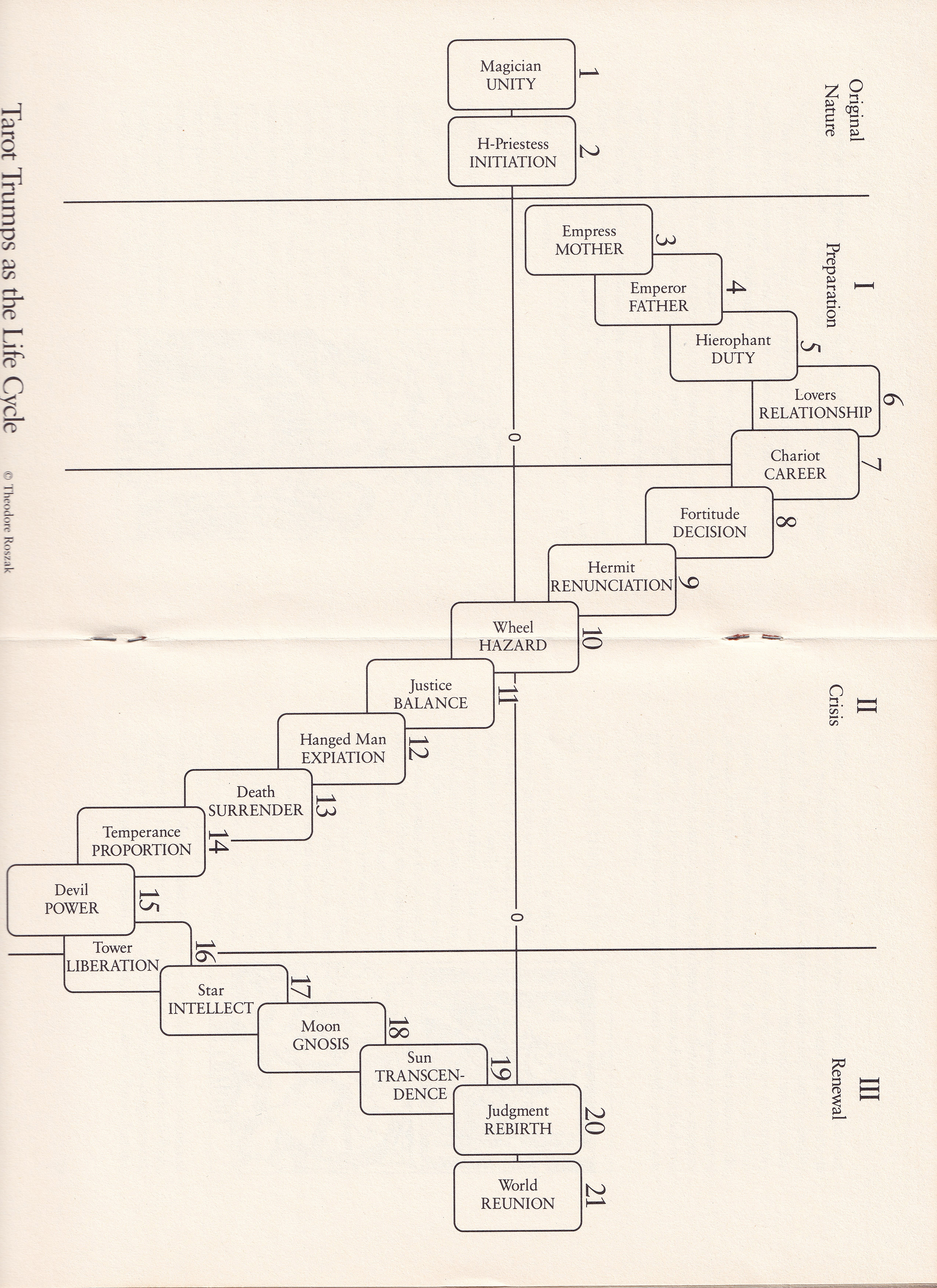

Fool’s Cycle / Full Cycle, 1988. Robert Briggs Associates. Subtitled “Reflections on the Great Trumps of the Tarot”. Also presented in Broadside Edition. *

Flicker, 1991. Summit Books of Simon & Schuster. *

The Voice of the Earth, 1992. Simon & Schuster.

Ecopsychology, 1995. Sierra Club Books. Subtitled “Restoring the Earth, Healing the Mind”. Roszak as editor.

The Memoirs of Elizabeth Frankenstein, 1995. Random House. For Elizabeth Frankenstein, Roszak was the first man to win the James Tiptree Jr. award, recognizing works in science fiction or fantasy that explore or expand the idea of gender.

America the Wise, 1998. Houghton Mifflin. Subtitled “The Longevity Revolution and the True Wealth of Nations”. Near the end of his career Roszak struggled to obtain a consistent publisher for a number of reasons. According to my sources, America the Wise was pitched to numerous publishers and finally sold to Houghton Mifflin in exactly enough time for it to be acquired by another publishing company, which then threatened Roszak’s rights to own, edit, and fully revise the manuscript. Longevity Revolution is really an expanded edition of America the Wise after Roszak and Berkeley Hill bought the rights back from Houghton Mifflin a few years later. Since they have different titles (for legal reasons), both are included here.

The Gendered Atom, 1999. Conari Press. Subtitled “Reflections on the Sexual Psychology of Science”. Provides good background for the writing of Elizabeth Frankenstein. Roszak was known to teach a class almost exclusively on Mary Shelly at Cal State.

Longevity Revolution, 2001. Berkeley Hills Books. Subtitled “As Boomers Become Elders”. See note on America the Wise above. I prefer this edition over the Houghton Mifflin copy. *

The Devil & Daniel Silverman, 2003. Leapfrog Press.

World, Beware!, 2006. Between the Lines. Subtitled “American Triumphalism in an Age of Terror”.

Making of an Elder Culture, 2009. New Society Publishers. Subtitled “Reflections on the Future of America’s Most Audacious Generation”. *

The Crystal Child, 2013. Argo Navis. Not currently available for sale.

***

My special thanks to Paul Kleyman, who was kind enough to take time out of his day and assist me with some questions regarding The Crystal Child, provide additional information and leads, and overall catalyze the writing of this article. His information and journalism can be found here.

— Will says, “The bomb has already dropped, and we are the mutants.”

header image by Brendan McCauley